Way back in your family history, about 300 generations ago, a caveperson relation of yours had to run ‘like the wind’ to escape something that was keen to eat them.

Having survived that situation, the next time they had to run away, they were better at it. Their body had adapted its ability. They could run faster, and the poor predator had to find a nice steak somewhere else.

‘Survival of the fittest’ is literal.

When you train, you can manipulate this adaptive ability to create great outcomes. You can go ‘faster, higher, stronger’ as the Olympic motto goes.

There are a number of tools you can use to validate or design a good training program.

These principles are acknowledged as the fundamental building blocks of exercise plan development which you can find in any introductory sports science or coaching text.

Any good plan must comply with these concepts.

Principle 1: Specificity

Here’s a no brainer. You get good at what you practice. If you practice running, your running improves. You can’t work on your juggling obsessively and expect it to change your running. You must be specific.

Best results are achieved by being specific about your goal and specific about the exercises you attach to it.

Principle 2: Overload

In the ancient Olympics, there was a famous champion called Milo of Croton. One day a calf was born in Milo’s village and so to build strength each day, he would lift the calf onto his shoulders. Over the next few years, so the story goes, the calf grew and matured until Milo was now heaving a fully-grown bull onto his shoulders. With more and more ‘beef’ being lifted, Milo adapted by becoming stronger and stronger.

Your body needs something to adapt to. Something that puts it under a little bit of pressure.

This ‘pressure’ can be an increase in duration or reps, (volume), an increase in effort (intensity) or by adding something different like a new skill (type) to your workout.

This Overload must be precise and is like the children’s story of Goldilocks and her 3 bears. Too little load and your body has no need to adapt. Too much load and get injured, ill or exhausted! Just the right load and your body will adapt by increasing its ability.

This increased ability to cope with load is called ‘Fitness’.

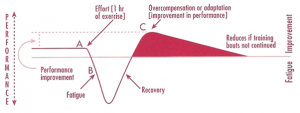

From the graph below:

- Starting at your current fitness level (Fig. 1A),

- You train which causes fatigue (B),

- As your body begins to recover, it doesn’t want to reach the same compromised state of fatigue in the future, so it rebuilds itself to a higher level of ability (C) – you get better (fitter or stronger).

Figure 1: Graph Depicting Overload; often called the Law of Overcompensation that Defines Physiological Adaption and Improvement.

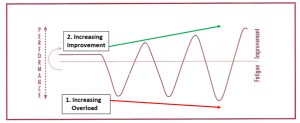

What this means is you need to keep adding load to give your body a reason to adapt and improve. (Fig. 2)

Figure 2: Continued Improvement Requires Continued Increases in Load

Let’s test that.

I’m sure you’ve heard the phrase, ‘insanity is defined as doing the same thing and expecting a different outcome’.

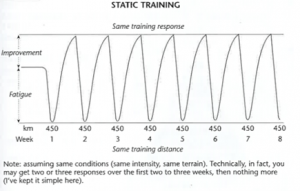

Let’s try a ‘thought experiment’ with the Overload graph. (Fig. 1)

- You do a 60min run and recover adequately.

- You get fitter.

- Now let’s repeat that 60min run at the same pace and duration followed by proper recovery.

- Do you get fitter?

- Let’s keep repeating this exercise/recovery regime, doing exactly the same workout for 2 months.

- Do you get fitter?

It’s a bit more complex than this but if you show your body something that it’s used to, there is no surprise, there is no need to adapt and nothing changes fitness wise. (Fig. 3)

Figure 3: Simplified Overload Graph Showing Maintenance Where Repetitive Bouts of the Same Load Result in the Same Fitness Response. (the Fine Print Says You Can Get Gains from the Same Training Load Repeated But it Follows the Law of Diminishing Returns Quickly.)

You will know someone who maybe ‘trains’ by doing the same run week after week. Technically they are not ‘training’. They are ‘maintaining’. No overload, no need to adapt! Simply, Overload is usually a combination of how hard you worked (Intensity) for how long (Volume). Basically:

Training Load = Intensity x Volume

Test to Analyse a Training Plan:

Is the plan showing a gradual increase is exercise workload?

Applying this to Writing a Training Plan:

-

- Volume: Build duration by 5-10% per week to the middle of your training plan and then drop it to about 2/3 of maximum for the remaining weeks.

- Intensity: Build the majority of intensity in the second half of your plan (i.e. last 3-7 weeks) – use intensities close to your target need (e.g. half marathon pace).

Principle 3: Exercise Types

Exercise is a way of explaining through your actions what you want your body to get better at. Think of it as ‘charades for cool people’! If you explain things well; by consistently showing your body something, it will adapt specifically to what you have shown it.

Keeping it simple, there are 4 basic Exercise Types you can use.

- Better Technique: show your body the perfect action until it becomes a pattern.

- Better Technique Endurance: show your body increasing durations of the skill until you can endure it for longer without deteriorating.

- Better Strength Endurance: show your body increasing resistances of the skill until it becomes strong enough.

- Better Speed Endurance/Speed: show your body higher speeds using the skill until it becomes fast enough.

Endurance in this case, can be defined as the duration or number of reps needed to complete the activity. There is a ‘Type’ of Activity designated as Technique, Strength or Speed and this to some extrent also defines the intensity and whether the emphasis is localised on the cardio or muscles. Fundamentally, we are manipulating ‘type’, ‘volume’ and ‘intensity’ to create improvement.

If these were strength exercises, we’d be talking about Skill, Muscle Endurance, Strength and Power.

Test to Analyse a Training Plan:

Does the plan contain all/most Exercise Types required to build a user’s ability?

Applying this to Writing a Training Plan:

The answers to the following questions choose what Exercise Types are emphasised within a training program:

- Event Length: Longer events favour Endurance and Strength emphasis within a training program. Shorter events favour Strength and Speed.

- Experience: Less experienced people respond better to an emphasis of the Technique and Endurance in their training program. More experienced people often respond better to Strength and Speed.

- Weakness: You usually get the biggest fitness/strength gains if you emphasise the weakest area of the Exercise Types.

Principle 4: Progression

You can’t improve in all 4 Exercise Types at the same time. If you think of exercise as a conversation with your body, it can’t hear 4 different ‘voices’ demanding attention at once. Better to hear things one at a time.

To achieve this, emphasise one ‘Type’ and maintain the others. Over time, the emphasis keeps changing following a logical order. This ‘emphasis’ builds improvement in an order where each new ability relies on the previous Exercise Type as it’s underpinning; skill precedes endurance, followed by strength and speed.

This law of Progression is often referred to as Periodization. (multiple periods of differing ‘emphasis’.)

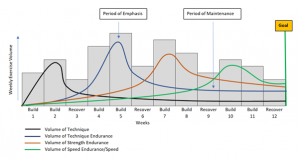

In the graphic below (Fig. 4) you can see how Progression applies to running.

Using a simple example, if you wanted to run a Marathon,

- you’d improve your running Technique,

- followed by building distance to somewhere near the event length (Technique Endurance),

- then add Strength Endurance which in this case is your ability to push yourself a greater distance per step known as stride length.

- Next, you’d move to turning that big stride length over faster by training your ability to increase stride rate. This long stride length at a high stride rate means Speed Endurance and Speed.

- Finally, you’d Taper and prepare yourself for the conditions and strategy required for the event (although you include this all the way through the progression as well.)

Figure 4: Graph Showing How the Principle of Progression Works for Marathon Running.

Test to Analyse a Training Plan:

Can you see the Progression in the plan? Can you see periods of different forms of emphasis; Periodization? Is it in the right order?

Applying this to Writing a Plan:

The rules of progressions are:

- If you are younger or a beginner, focus mostly on Technique and Endurance.

- If you have intermediate experience, focus on Endurance and Strength mostly.

- If you are experienced, focus on Strength and Speed.

- Always emphasise the weakest area.

Usually, periods of 2-4 weeks should be spent on each phase. Too short and your new superpowers don’t get bedded in and too long and you tend to plateau wasting time. Because your body is ‘reacting’ to what you give it, you keep the ‘surprises’ coming.

Principle 5: Recovery:

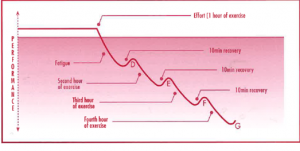

Let’s go back to the Overload graph.

Using the graph, let’s do another ‘thought experiment’:

- You go out to exercise by doing a 60 minute run. Immediately after the 60min, are you better or worse?

- Worse! You are fatigued. (D Fig. 5 below)

- Let’s make you immediately do another 60 minutes of exercise. What happens after this bout, are you better or worse?

- Worse again, you are even more tired! (E)

- Let’s repeat this 5 more times, each time adding another 60 minutes of exercise. What happens?

- Yikes! You just keep getting worse. (F and G)

Figure 5: Graph Showing How Lack of Recovery Leads to a Drop in Performance/Fitness

Look back at the previous bullet points and you’ll see the words ‘exercise’ and ‘worse’ in bold. Every time I mentioned that you do another 60min of exercise YOU AGREED it made you worse! Here’s the kicker, what you are saying is “exercise makes you worse”!!!!! AND before you cry foul, think about that because……you are right!

Question: Exercise breaks you down, it fatigues you…what builds you back up?

Answer: Recovery!

It’s exercise and then the ability to recover that causes your body to rebuild and then adapt as we saw in the Overload graph.

Exercise + Recovery = Improvement

There is no such thing as a good training plan – it must be a good training AND recovery plan. How many people do you know that only understand half this equation?

There are 3 techniques used in Training Plan design. Each involves a cycle of Load and Recovery.

1. Microcycle:

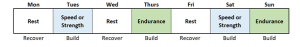

The first is the weekly Day-to-Day Microcycle which has 2 rules:

a. Build-Recover Rule: Basically, it means always follow a loaded workout (build) with a recovery workout or rest (e.g. Build day, Recover day in Fig. 6):

Figure 6: Microcycle Build-Recover Rule in Practice.

Even in a more complex situation, the basis of this rule is maintained where the least number of ‘Build’ days occur in a row before returning to a recovery day.

b. Keep ‘like’ workouts apart: while keeping to the Build-Recover rule, always keep similar Exercise Type workouts as far apart from each other as possible to maximise recovery as shown below. (Fig. 7)

-

- Keep Rest days away from each other.

- Keep Technique Endurance days as far apart as possible.

- Keep Speed Endurance and Strength Endurance days separated.

Figure7: Microcycles Showing the Allocation of Exercise Types to Ensure Maximum Recovery.

Not all exercise that you do makes you better. As we’ve discussed, if you don’t recover, you don’t improve. Maximising your recovery allows you to ‘absorb’ the maximum benefits from each workout. (i.e. more result for time spent).

Test to Analyse a Training Plan:

Do the rest days look balanced and are the Exercise Type days separated correctly?

Applying this to Writing a Plan:

Workout Frequency using Microcycle rules:

- Beginners and Recreational: should exercise 3 times per week. If busy, 2 times will work.

- Semi competitive: 3 – 4 times per week.

- Competitive: 4 – 5 times per week.

- Advanced: 5 – 6 times per week.

Expect higher workout frequency for Endurance and lower for Speed phases.

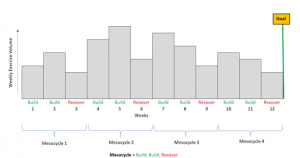

2. Mesocycle:

You will also accumulate fatigue over weeks. To deal with this, Mesocycles are used and usually set at two Build weeks of exercise followed by one Recovery week. (Fig. 8)

Figure 8: Graph Depicting a Training Plan Made Up of 4 Mesocycles (Build-Build-Recover Weeks).

Test to Analyse a Training Plan:

Are there recovery weeks or does the training program keep ramping all the time?

Applying this to Writing a Plan:

Almost everyone operates best on 2 Build weeks and 1 Recovery week. Very experienced exercisers could do 3 Build weeks and 1 Recovery week.

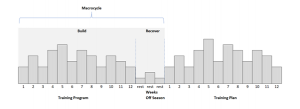

3. Macrocycle:

There is a peculiar effect that blurs the logic of exercise improvement. If you are doing the best possible training plan and exercise for many many weeks in a row 3 things happen:

- Initially there is a Training Effect as you improve in reaction to exercise stress (6-12 wks).

- After a period, no matter how optimal the training plan, you’ll start to plateau leading to a Maintaining Effect (from approx. 14-20 wks).

- If you keep going, you’ll reach a point where there is deterioration of your ability despite doing optimal exercise. This is an Overtraining Effect. (from approx. 20+ wks)

There is a good time to train BUT there is also a good time to stop too!

Macrocycles are the largest Build-Recovery planning tools to control build ups of long-term fatigue and are made up of a training program (Build) plus an Off Season (Recovery) period afterwards. (Fig. 9)

Figure 9: Graph Showing the Make Up of a Macrocycle (Build-Recover)

It’s in your Off Season’s that you recover and gather enough energy to be able to extract more fitness/strength gains out of the next training program. It seems counter intuitive that you’d schedule periods where you lose some fitness! BUT you don’t lose all your fitness and start back at the beginning. You lose some fitness but start the next training program fitter than the start of the previous block and fresh enough to absorb even more gains. This means that over a year, correctly balanced Off Seasons lead to fitness scalloping up to higher abilities. (Fig. 10)

Figure 10: Fitness Increasing Over Successive Macrocycles.

Conversely, if the Off Seasons are poorly planned, poorly executed or don’t exist, your physical abilities remain static and in certain situations deteriorate due to fatigue.

It’s possible to Overtrain 2 different ways;

- too much (Volume), too hard (Intensity) or too different (Type) over a workout or week (Easy to Notice).

- or unrelenting low-grade overload over months and sometimes even years (Harder to Notice).

Test to Analyse a Training Plan:

Are there periods of longer-term rest? Are these periods 2 or more weeks long? Are the programs usually between 6 and 12 weeks in length?

Applying this to Writing a Plan:

Program Length: Program lengths vary between 6 and 14 weeks depending on a number of things:

- Life Load/Physical Status: High Life Load or reduced Physical Status means shorter programs and low Life Load or optimal Physical Status means longer programs.

- Event Length: Longer events (e.g. marathon) often mean longer programs and short events mean shorter programs.

- Experience: More experienced exercisers often fare better with shorter programs. Less experienced exercisers often need more ‘runway’.

- Drive: Driven people push themselves much harder and need shorter programs. More laid-back individuals can cope with longer program.

The combined answers to these questions set the program length; long (12-14 weeks), medium (9 – 10 weeks) and short (6-7 weeks) depending on the person.

Off Season Length: These same rules decide Off Season lengths (2-4 weeks) with one addition; the biggest goal event of the year ideally has the biggest rest afterwards. (think Olympics at 6 – 8 weeks.)

Number of Macrocycles per year: Usually 3 – 4 macrocycles per year are best and the major emphasis should change in each macrocycle to promote maximum fitness/strength gain.

Principle 6: Reversibility

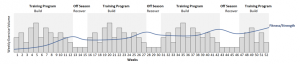

Finally, if you don’t continue to practice an ability, you lose it over time (i.e. use it or lose it). Your fitness/strength is reversible. Juggling at least 4 Exercise Types, the law of specificity says you get good at what you practice, and the fine print says training different stuff means you start to lose what you trained previously.

We’ve discussed maintenance already and it’s a very important tool to keep what you have already built up. You can reduce the maintenance volume of an Exercise Type down to about 30% of a previous maximum and still get your body to hold the ability for an extended period.

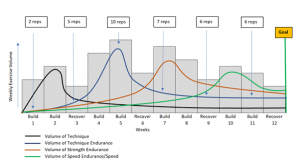

Following the logic of Progression, we emphasise an Exercise Type while maintaining everything else. For example, we emphasise Strength Endurance and maintain Technique, Technique Endurance and Speed Endurance. Each Exercise Type takes it’s turn at emphasis while other Types are held in maintenance. (Fig. 11)

Figure 11: Graph Depicting Emphasis and Maintenance of Different Exercise Types in Order Over a Training Plan.

Test to Analyse a Training Plan:

Can you see training AND maintaining in the program over time?

Applying this to Writing a Plan:

Understanding the above methodology means that a training program can be easily written. Just set the reps for each Exercise Type to follow the waves shown in the graph. You have now written your program! (Fig. 12)

Figure 12: Graph Showing How Each the Emphasis-Maintenance Wave for Each Exercise Type Outlines the Volumes Applied to the Reps for Each Week of Training.

Summary:

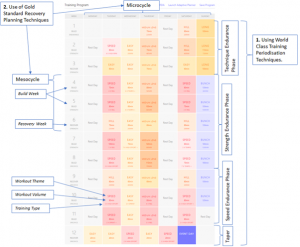

These 6 universal exercise principles maximise your improvement returns for time spent. They can be incorporated to:

- optimise your Training Plan,

- or they can be used to analyse the efficacy of a Training Program you are considering following.

They a fundamental to the science/coaching methods of Smart Training. (Fig. 13)

Figure 13. Elements of the Performance Lab Workout Planner Showing Periodization Methodologies.